Image 1 of 2

Image 1 of 2

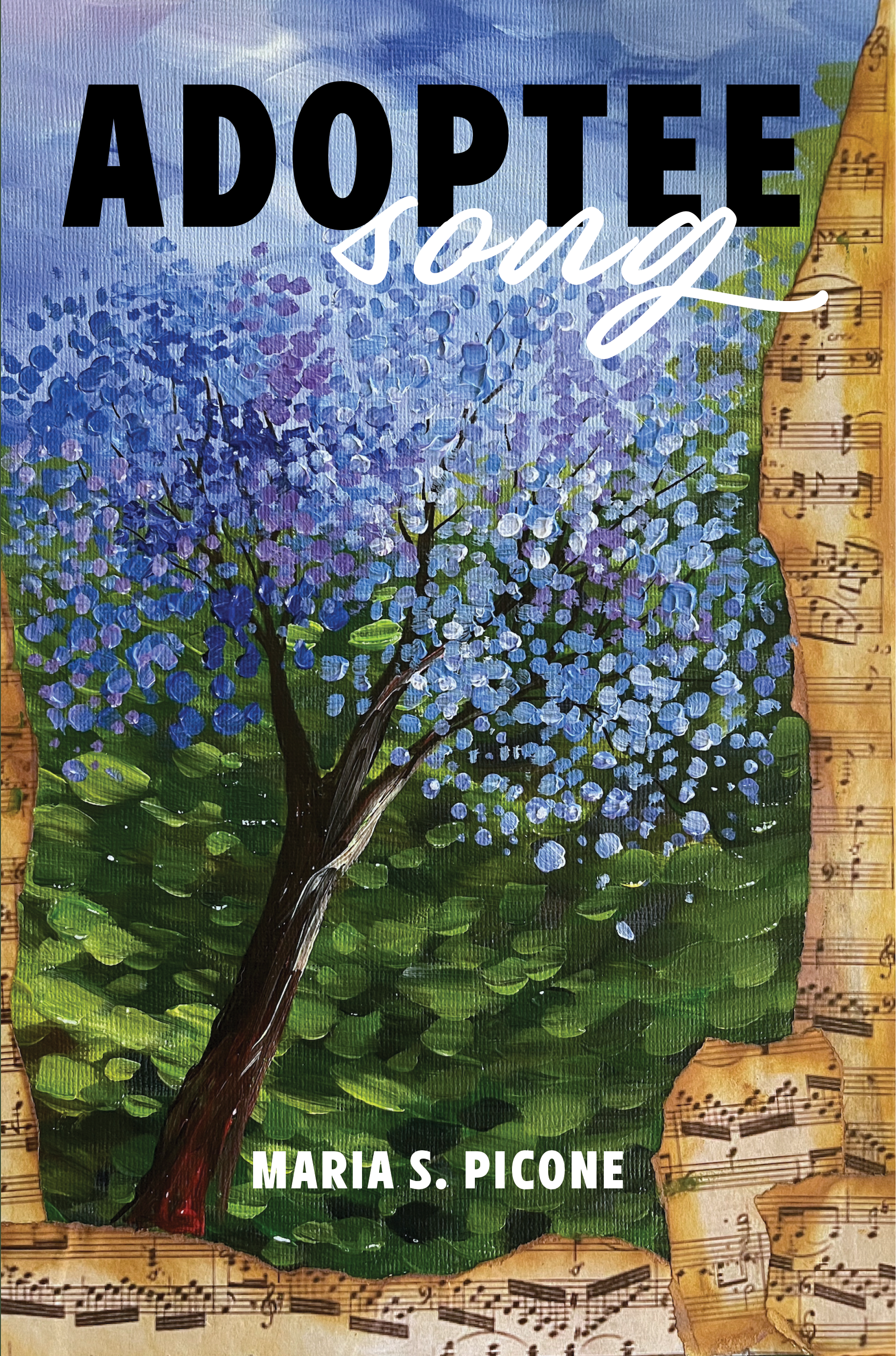

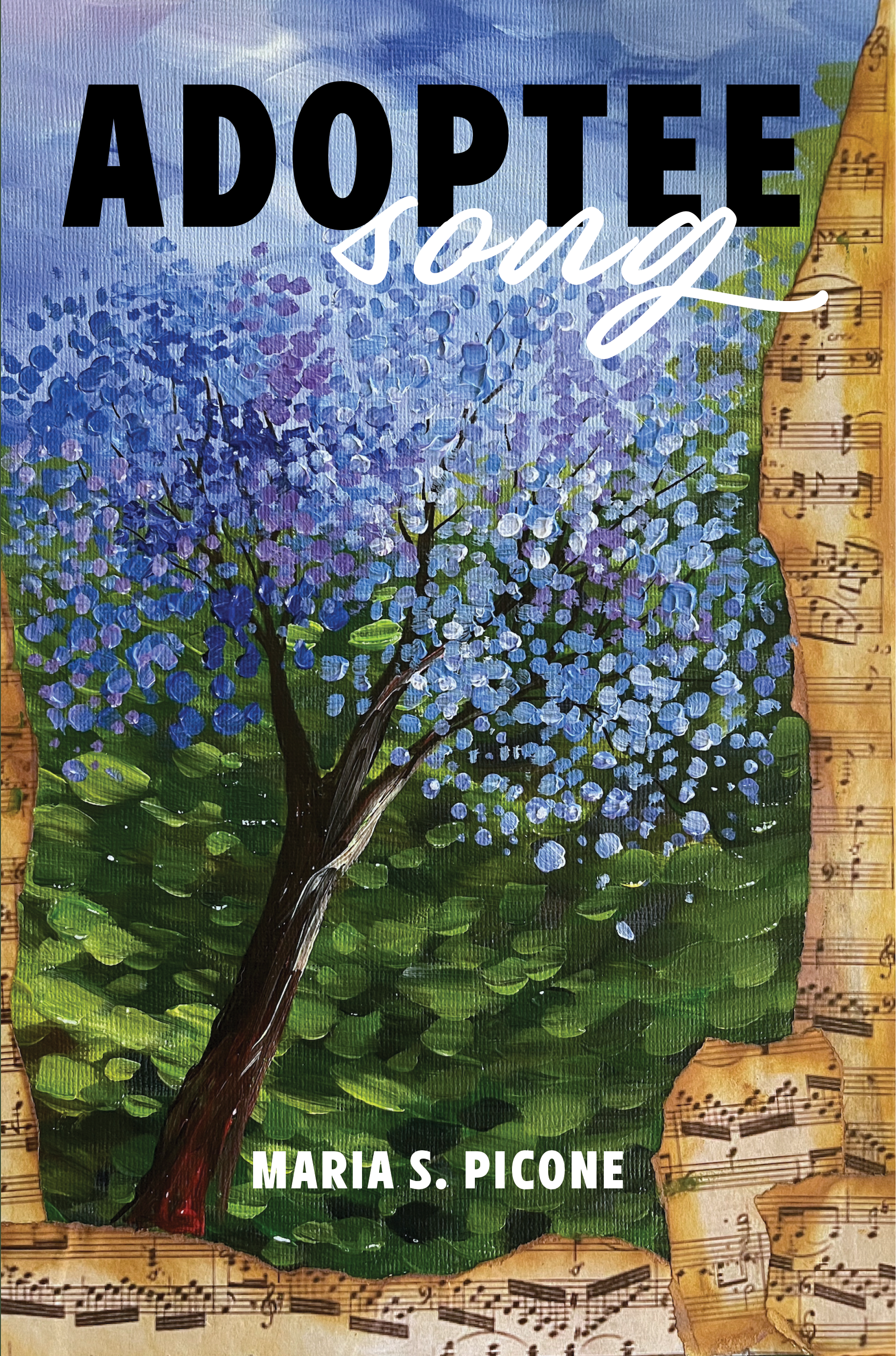

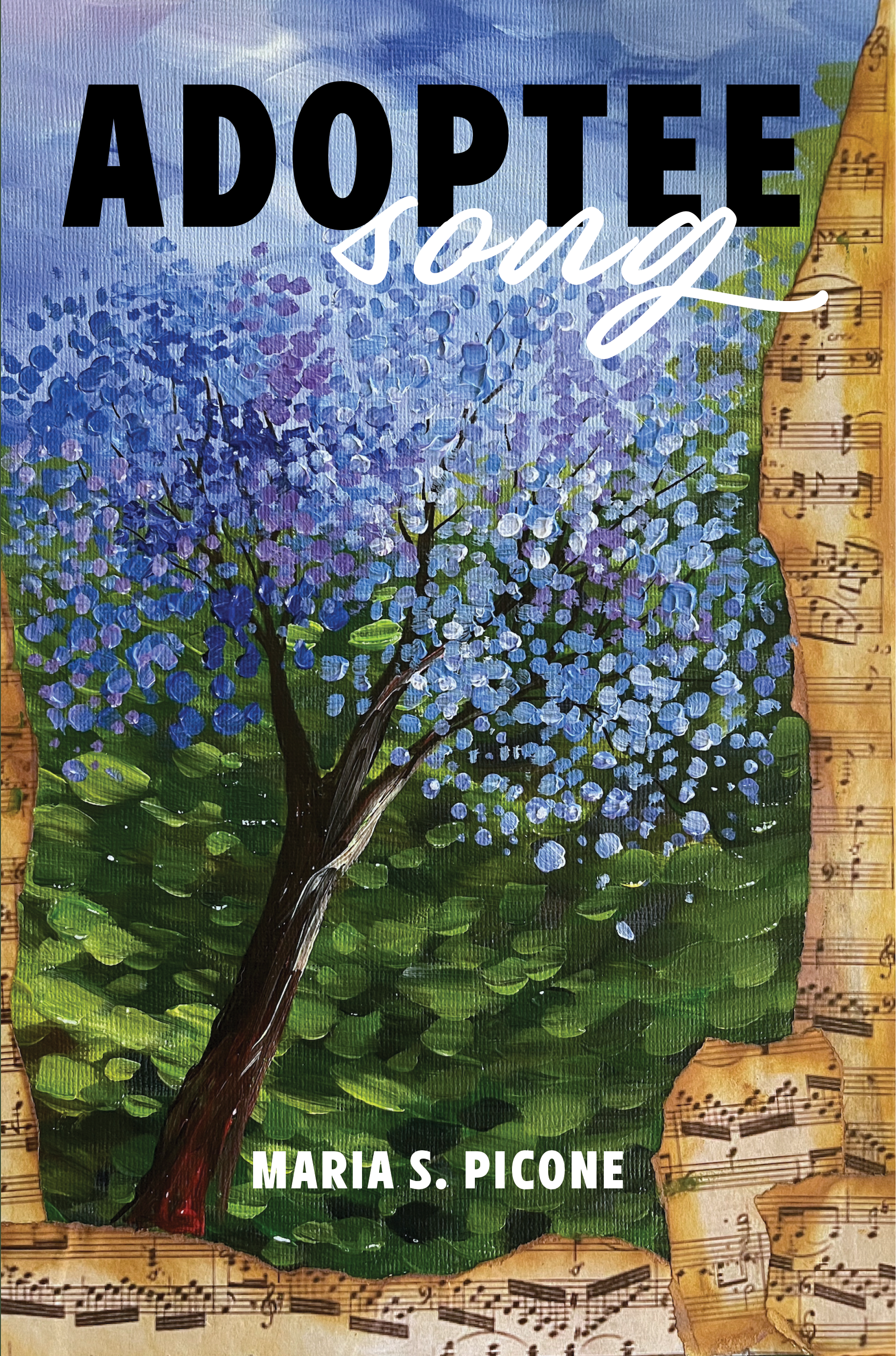

Adoptee Song — Maria Picone

Praise for Adoptee Song

“Adoptee Song is an instant fixture in my Korean American and adoption poetry canon. Maria Picone’s stunning poems seem effortless but began, I imagine, a hundred years ago: to know the self, erasure, guardian angel, love. This is a singular, brilliant music of grace, survival, and self- acceptance, that is to say: a new, redemptive, breath-taking poetry.”

—Lee Herrick, California Poet Laureate and author of Scar and Flower

“In this confrontational collection, Maria Picone tunes her lyric to dissect and interrogate the transnational and transracial adoptee experience of a Korean child adopted by a white American family. From the opening lines, we learn that this is not An American Tail with a happy ending, but that the speaker is ‘like a good villain’ who will ‘rail against [her] ending.’ Here are poems which plumb the facts of an adoptee’s life, a foreign language which could have been a mother tongue; Picone’s startling enjambments reflect the fractures of identity at the levels of language, culture, and race, and her poems, despite their frankness (‘You weren’t an abortion’), contain multitudes, contradictions, and dualities: ‘I have two names. I do not have two names.’ With Adoptee Song, Picone has composed a masterful epic: these poems exist as a primer of resilience and survival not only for the speaker, but for all those who don’t feel like they belong.”

—Diana Khoi Nguyen, author of Ghost Of

“‘I have no idea how it coheres.’ This searingly honest line in the tellingly titled ‘History of Adoption in Korea Maria’ primes us for the intellect, music, and central query of Adoptee Song. Is it possible for multiple senses of identity to cohere? Is there logic to be found in incoherence? In poems that range from playfully experimental to experimentally intentional, Maria S. Picone writes of ‘two different names,’ declaring ‘I am the eternal river, perpetuity of mirrors flowing forever’ (“朝鮮姓名復舊令”). This tendency towards multiplicity, perpetuity, is reflected in Maria’s authorial strengths: dense syntax that refuses white legibility, fearless engagements with a wide array of free verse forms, and an appreciation of word play that I firmly believe can only come from those of us to whom English and/or America remain, permanently, at arm’s length.

But keeping the reader at arm’s length does not interest Maria as a poetic approach. Reader, I have found myself saying the word ‘generous’ a lot these unwinding ‘post’-pandemic days—thanking those around me for their time, attention, care. So I thought quite intentionally about using it here. I asked myself, ‘Am I simply defaulting back to calling Maria’s writing generous because it is the easiest thing to say?’ On a third, fourth, fifth read of this chapbook, I determined such a critique could not be leveraged. For Maria is a generous writer—and these poems are outpourings of that generosity. Not just in her willingness to—even insistence on—painting for the reader an incredibly detailed picture of the intersections of her identity; no, Maria’s generosity is syntactical, formal, imagistic, sonic, feminist. What she says she is in these poems, she gives us in this chapbook: ‘another shell on the reef: another shell’ (Hypnerotomachia).

To read Adoptee Song is to be rocked by a lullaby of lost worlds, to be held in the place between slumber and attention; as she writes in the poem ‘History of Adoption in Korea Maria,’ ‘I became a doorway without country, swinging open and shut.’ Indeed, Maria’s language swings open and shut throughout the text, crossing through phrases to comment on a culturally mixed identity as in ‘the rough draft of my life,’ including the Korean alphabet and explicit commentary on her limited understanding of it throughout the text. I am grateful for these poems—how direct and incisive their knowledge of both the self and the self’s limitations, how playful they can be, and ultimately, how honest they are about their version of the Asian American experience. As Maria writes of our complexities and contradictions in ‘For my own 34th Birthday,’ ‘I can say it in twelve languages but I can never answer.’”

—Raena Shirali, author of summonings

Praise for Adoptee Song

“Adoptee Song is an instant fixture in my Korean American and adoption poetry canon. Maria Picone’s stunning poems seem effortless but began, I imagine, a hundred years ago: to know the self, erasure, guardian angel, love. This is a singular, brilliant music of grace, survival, and self- acceptance, that is to say: a new, redemptive, breath-taking poetry.”

—Lee Herrick, California Poet Laureate and author of Scar and Flower

“In this confrontational collection, Maria Picone tunes her lyric to dissect and interrogate the transnational and transracial adoptee experience of a Korean child adopted by a white American family. From the opening lines, we learn that this is not An American Tail with a happy ending, but that the speaker is ‘like a good villain’ who will ‘rail against [her] ending.’ Here are poems which plumb the facts of an adoptee’s life, a foreign language which could have been a mother tongue; Picone’s startling enjambments reflect the fractures of identity at the levels of language, culture, and race, and her poems, despite their frankness (‘You weren’t an abortion’), contain multitudes, contradictions, and dualities: ‘I have two names. I do not have two names.’ With Adoptee Song, Picone has composed a masterful epic: these poems exist as a primer of resilience and survival not only for the speaker, but for all those who don’t feel like they belong.”

—Diana Khoi Nguyen, author of Ghost Of

“‘I have no idea how it coheres.’ This searingly honest line in the tellingly titled ‘History of Adoption in Korea Maria’ primes us for the intellect, music, and central query of Adoptee Song. Is it possible for multiple senses of identity to cohere? Is there logic to be found in incoherence? In poems that range from playfully experimental to experimentally intentional, Maria S. Picone writes of ‘two different names,’ declaring ‘I am the eternal river, perpetuity of mirrors flowing forever’ (“朝鮮姓名復舊令”). This tendency towards multiplicity, perpetuity, is reflected in Maria’s authorial strengths: dense syntax that refuses white legibility, fearless engagements with a wide array of free verse forms, and an appreciation of word play that I firmly believe can only come from those of us to whom English and/or America remain, permanently, at arm’s length.

But keeping the reader at arm’s length does not interest Maria as a poetic approach. Reader, I have found myself saying the word ‘generous’ a lot these unwinding ‘post’-pandemic days—thanking those around me for their time, attention, care. So I thought quite intentionally about using it here. I asked myself, ‘Am I simply defaulting back to calling Maria’s writing generous because it is the easiest thing to say?’ On a third, fourth, fifth read of this chapbook, I determined such a critique could not be leveraged. For Maria is a generous writer—and these poems are outpourings of that generosity. Not just in her willingness to—even insistence on—painting for the reader an incredibly detailed picture of the intersections of her identity; no, Maria’s generosity is syntactical, formal, imagistic, sonic, feminist. What she says she is in these poems, she gives us in this chapbook: ‘another shell on the reef: another shell’ (Hypnerotomachia).

To read Adoptee Song is to be rocked by a lullaby of lost worlds, to be held in the place between slumber and attention; as she writes in the poem ‘History of Adoption in Korea Maria,’ ‘I became a doorway without country, swinging open and shut.’ Indeed, Maria’s language swings open and shut throughout the text, crossing through phrases to comment on a culturally mixed identity as in ‘the rough draft of my life,’ including the Korean alphabet and explicit commentary on her limited understanding of it throughout the text. I am grateful for these poems—how direct and incisive their knowledge of both the self and the self’s limitations, how playful they can be, and ultimately, how honest they are about their version of the Asian American experience. As Maria writes of our complexities and contradictions in ‘For my own 34th Birthday,’ ‘I can say it in twelve languages but I can never answer.’”

—Raena Shirali, author of summonings

Maria S. Picone is a queer Korean American adoptee who won Cream City Review’s 2020 Summer Poetry Prize and Salamander’s Louisa Solano Memorial Emerging Poet Prize. She has two forthcoming chapbooks, Adoptee Song (poetry, Muddy Ford Press) and Propulsion (fiction, Conium). Maria was published in Best Small Fictions 2021, Vestal Review, Orca, Reckoning, Cherry Tree, and more. She has received support from Juniper, Hambidge, SCAC, Lighthouse Writers, GrubStreet, Kenyon Review, and Tin House. She is Chestnut Review’s managing editor, and edits at Uncharted, The Seventh Wave, and Foglifter. She holds an MFA from Goddard College. Website: mariaspicone.com; socials: @mspicone.